The Visibility Gap in Agentic Design Work (AI Systems and UX)

The most consequential design work now happens in guidelines for AI agents and system orchestration—but our profession has no way to evaluate, reward, or even see it.

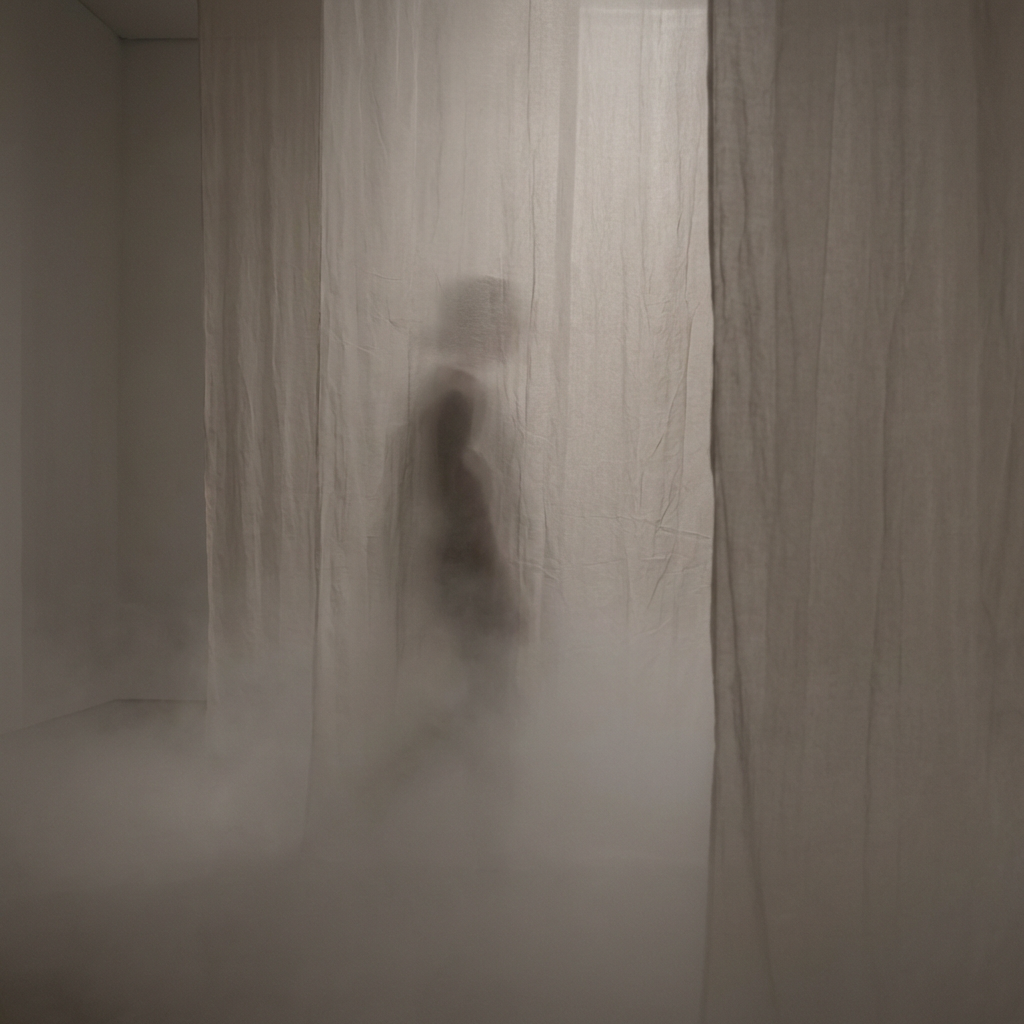

The visibility gap in agentic design work

Why AI-powered, systems-level design work is becoming harder to see — and harder to evaluate

This week I’ve been working on a feature that needs to show busy professionals a quick snippet of the top three to five insights they should take action on. Simple enough, but I can’t show it to my cross-functional partners without having an opinion on which insights get surfaced and why. I can’t just design a card layout and call it done, because the hard question is how the system knows which insights matter most to each user at any given moment — a problem that’s increasingly common in AI-powered, agentic products — and how I communicate that to my cross-functional partners.

What agentic systems actually require from design

I had foundational user research that told me what areas of users’ work they care about, as well as the signals they themselves use to decide what feels important. The design problem was not translating that research into a UI, but deciding how those human priorities should be interpreted, weighed against one another, and acted on by a system. I needed to spell that out in a way engineers could translate into code, while still preserving the value judgments embedded in the research.

Here was my proposal—

- We have specialized AI agents for each area of user priority that collect signals and observations according to the user criteria of importance.

- We pass all of those signals to a normalization agent that looks for patterns and overlap in common entities and events and then synthesizes them into mutually exclusive “stories.”

- We pass those “stories” to a ranking agent that understands what is urgent and impactful to our users and prioritizes and surfaces them accordingly

I spent hours creating guidelines, not because the system was technically complex, but because the decisions were. I had to think through how the system should weigh urgency against long-term importance, how it should resolve ties between competing priorities, how much recency should matter relative to consequence, and what it means for an insight to be truly actionable for a busy professional. Much of that thinking took the form designers are already familiar with: exploring edge cases, rehearsing failure modes, and testing where a set of rules would break under real-world conditions. Physically, the work took up a significant amount of space in Figma as I mapped out decision boundaries and documented the reasoning behind them. Over the next few weeks, I’ll discuss this with my teammates, show it to users, and iterate—not primarily on how it looks, but on whether the system’s judgments align with what users actually need. This kind of decomposition and re-ranking is a common pattern in agentic workflows, where multiple AI agents contribute signals that must be synthesized into a single, user-facing point of view.

The collapse: old becomes new

All that work for just a few cards with buttons. An enormous amount of thought and process and intention go into something, and at the end, it collapses into a a small piece of UI at best, and now, increasingly, a paragraph of text delivered to the user by an LLM.

Designers have always dealt with collapse. Figma frames and prototypes are themselves compressions of thought, where hours of exploration and iteration get distilled into a handful of screens and a clickable flow. But those were necessary collapses that still produced something tangible to show. You could point to the prototype, walk someone through the frames, explain the visual decisions and interaction patterns, and the artifact itself validated that the thinking had happened. The progression from sketches to wireframes to high-fidelity mockups made the design labor visible and legible, both to stakeholders who needed to understand the work and to the profession itself, which has long defined and valued design through these kinds of artifacts. The collapse was real, but the output was still something you could put in a portfolio, something that demonstrated craft and judgment in a form the industry knows how to recognize.

This is not new in enterprise platform design

What I’m describing here doesn’t actually feel entirely new to me. I’ve been working in enterprise platform design for years, in environments where the core job is not designing a single, controlled experience but designing within a system that customers will inevitably configure, extend, and sometimes break. A large part of the work is anticipating variability, defining guardrails, and doing your best to ensure that the design holds up even when you cannot predict exactly how it will be used.

That kind of work already produces a collapse of visibility. When you’re designing for platforms rather than products, much of your effort goes into constraints, defaults, escalation paths, and failure prevention. If you do that work well, the experience feels stable and flexible at the same time, and there’s very little to point to visually. The traces of your judgment are distributed across the system, embedded in rules and behaviors rather than concentrated in a single artifact.

There is also a very real industry bias layered on top of this. The design profession, its hiring practices, and its portfolios are still heavily oriented around consumer work, where the artifact is the thing. Screens, flows, and polished interfaces are treated as the primary proof of skill. Enterprise designers who spend their time working at the system level often struggle to translate their work into those terms, which creates a subtle but persistent credibility gap. It’s not uncommon for that gap to feel like a ceiling: work that is complex, consequential, and difficult gets flattened or undervalued because it doesn’t conform to the dominant artifact-driven model.

What feels different now is that AI is pushing this dynamic out of enterprise platforms and into many more kinds of products. As experiences become more adaptive, probabilistic, and agent-driven, consumer designers are being asked to design for uncertainty, orchestration, and behavior rather than fixed flows. In other words, they are being pulled into the same kind of systems thinking that enterprise designers have been practicing for a long time. The visibility problem isn’t new, but it’s about to become much more widespread.

When design moves beyond pixels

The agentic work I described earlier feels like a continuation of this same pattern, just in a new technical register. What’s happening now feels different, because the work is still design. I’m still designing the experience, the prioritization logic, the user’s relationship to information, but the output isn’t pixels anymore. It’s guidelines for AI agents, ranking criteria, orchestration logic that determines how different systems talk to each other and make decisions on the user’s behalf. The thinking is the same depth, maybe even deeper, because I’m not just deciding what appears on a screen but how an entire system reasons about user needs and makes choices in real time. But there’s nothing tangible to show for it in the way the profession currently understands design artifacts. When I finish designing that ranking agent’s behavior, I have a document with guidelines and decision criteria, but I don’t necessarily have frames to walk through or an interactive prototype to demonstrate. Or if I do it feels increasingly contrived. The compression ratio has changed dramatically: weeks of thought about user priorities, edge cases, failure modes, and value judgments collapse into a few sentences that instruct an agent how to behave.

The visibility gap

I keep thinking about what this means for how design work is understood and valued, because design has historically been defined through its artifacts—the mockups, the prototypes, the design systems, the polished interfaces that demonstrate both craft and strategic thinking. But if the most consequential design decisions now happen at the system level, in the guidelines that shape how AI agents prioritize information or the logic that determines what gets surfaced to users and when, then those traditional artifacts no longer represent the most important work. This creates what I think of as a visibility gap in AI and systems design: the design labor that has the most impact on user experience is increasingly the least visible. It’s not just an individual portfolio problem, though it certainly is that—how do you show the depth of thinking behind a ranking algorithm’s guidelines, or demonstrate the judgment embedded in agent orchestration logic? But it’s also a profession-wide challenge in how we represent, evaluate, and reward design work that doesn’t produce pixels.

Recognition, leverage, and career signal

The work review I wrote for myself a few weeks ago noted that I “naturally gravitate toward meta-work that creates future leverage—systems, workflows, frameworks,” and that observation feels even more relevant now. I build systems that create real value and compound over time, but the visibility problem remains: if no one can see the work, including the people who evaluate my performance or the profession that decides what counts as design, then how does that labor get recognized? I’m not the only one doing this kind of work. I see it across the industry as design increasingly intersects with AI and system-level decision-making, but I don’t think we’ve collectively figured out how to make this work legible in the ways that matter for careers, for advancement, for the profession’s understanding of what design encompasses.

An open question for the profession

Either design needs to develop new ways to make this work visible—new documentation practices, new artifact types, frameworks for demonstrating system-level thinking that carry the same weight as a polished prototype—or there need to be adjacent roles and career paths for people doing this orchestration work, with their own evaluation criteria and advancement structures. The question isn’t whether this transformation is happening, because it clearly is. More designers are working on agentic systems, prompt engineering, AI behavior design, and orchestration logic, and that work requires all the judgment and user-centered thinking that traditional interface design requires. But the profession hasn’t caught up to this shift. We still evaluate design work primarily through visual artifacts, we still build portfolios around mockups and prototypes, we still use frameworks that assume design labor produces something you can screenshot and put in a slide deck.

The work is becoming more strategic and potentially more impactful, because designing how AI serves users, how systems make decisions on their behalf, and how experiences adapt and prioritize in real time is arguably more consequential than any individual interface decision. But simultaneously it’s becoming more opaque and harder to show. I can spend a week thinking through the ranking logic for that insights feature, and at the end I have a paragraph of guidelines that contains enormous amounts of judgment about what users need, how to balance competing priorities, and what tradeoffs to make. But that paragraph doesn’t look like much. It doesn’t signal the depth of thought that went into it the way a carefully crafted prototype does. And I don’t know how to resolve that tension, or whether the profession knows how to resolve it either.

I keep coming back to this question: as design work shifts toward agentic orchestration and system-level decision-making, how do we make that labor visible—not just for individual career purposes, not just so people like me can demonstrate the value of what we’re building, but so the profession itself can recognize, develop, and reward this kind of thinking? Because right now we’re in a transitional moment where the most consequential design work increasingly happens in spaces the profession doesn’t have good tools to evaluate, and I don’t think we’ve figured out what comes next.